Father’s day came and went without a ripple in the waters of grief for me. I never know from one year to the next how this day will land in my body. It’s going on seventeen years now without my Papa — over 6,000 days — and I simply can’t compute this length of time.

Papa was far from perfect. I know this is stating an obvious truth, but it feels important for me to name it. He struggled to be emotionally available and often hid behind sarcasm. He had deep wounds from his childhood, the patriarchy and religion that manifested in repressed addiction and changed our family in irreversible ways. He was a product of his fundamentalist evangelical upbringing, as much as he pushed the limits. He made devastating mistakes.

But I loved him fiercely.

For years after his death, I heard from my mom and sister that I “idolized” his memory. They saw me writing and sharing about my grief, of missing him, and it seemed they couldn’t reconcile this with my lack of sharing about them in a similarly positive way. I felt I needed to justify why I missed my dead dad to my living family and that seemed clearly about them, not me.

But the other truth is, I write about my Papa because the way he loved me felt more spacious, less judgmental, than anything I’ve felt from my other family members. He and I were also similarly wired: dreamers, artists, curious about others’ lived experiences, a mixture of quiet observer and life-of-the-party, coloring outside the lines, uninterested in being boxed in.

Which is ironic, considering he was a pastor of various conservative evangelical churches for many years.

Papa died before I married a man and spent eight traumatic years with him. Before I deconstructed the religious beliefs that were my birthright and walked away from Christianity entirely. Before I swung far left from my family in politics. Before I called the end of my marriage and moved across the country, several thousand miles from family. Before I told my sister I loved her, but I didn’t see how we could have a relationship as long as she saw me as nothing more than an “angry Christian-hater.” Before I came out as queer. Before my mom chose her religion over me and we stopped talking. Before I came out as a they/them and trans. Before I became Phoenix.

So really, I will never know if my Papa would have been able and willing to evolve with me.

What I do know is how I felt with him. How, even as a twenty-something adult, I never tired of tucking in next to him on the couch and feeling the warm weight of his arm around me. I miss how he listened to me in his quiet way and never co-opted my emotions with his own. He didn’t need anything from me; I could just be his kid. And not only that, I was allowed to be an autonomous person.

These were fundamental bricks in the foundation of my experience of him, and so, even with the monumental leaps that would have been required of him, I can’t help but think, He would have done it for me.

He may never have fully understood or shared my beliefs, but I feel he would have wanted to continue knowing me. It’s more than I can say about the rest of my family.

This, I wish to say, is why I wrote and wrote about him after he died. This is why, to this day, he remains my closest family member, even in his death.

. . . . . .

The last time I saw Papa alive, we were painting a garage together on a hot summer day. I had already graduated with my Master’s in counseling and was several weeks from finishing my yearlong internship as a bereavement counselor. We were talking about my plans: I would move to Minneapolis after I finished and he would drive with me.

As I talked, though, I found myself confessing to him something I hadn’t yet admitted to myself.

“I know it’s strange, having put all this work into this counseling degree… but what I really wish for, at the end of all this, is simply to write. Is that awful?” I chewed my lip and flicked my eyes to his nervously.

His face didn’t convey any shock at this admission. He smiled in his soft way. “Then you should write.”

I remember the weight that fell off of me in that moment, the possibility that breathed into empty space.

When I said goodbye to him, it was like any other day. I hugged him and walked away, believing I’d see him again tomorrow.

The call that woke me up early the next morning shattered my world. He had fallen from a ladder while painting on his own. Now he was in a coma.

I remember driving to my mom’s work to tell her the news because I couldn’t imagine making that phone call. I remember showing up to the hospital to see him unconscious with bandages around his head, covering a piece of his missing skull to relieve the swelling. I remember how calm I felt I had to remain while my mom came undone.

I remember curling up next to him in his hospital bed, gingerly stroking his paint-flecked hand around the tubes, whispering to him, Please wake up.

I remember the hours of saying goodbye while he left this earth and feeling I might die with him from the grief.

The grief has not shrunk in seventeen years, though it lives deeper beneath the surface than it used to.

. . . . .

I was browsing online for summer sandals yesterday while I waited for the subway when the grief bubbled up, snatching me like a riptide. I guess I didn’t make it through without ripples after all.

It was men’s sandals, to be precise. Picture after picture of sandals that reminded me of his. Suddenly, I was crying in the subway, below the streets of Brooklyn. I slipped my phone into my pocket, unable to keep looking.

He did that faux paus thing that men of a certain age often do where he wore socks with sandals. He hated showing his toenails. It was weird and unfashionable and I miss this more than I knew.

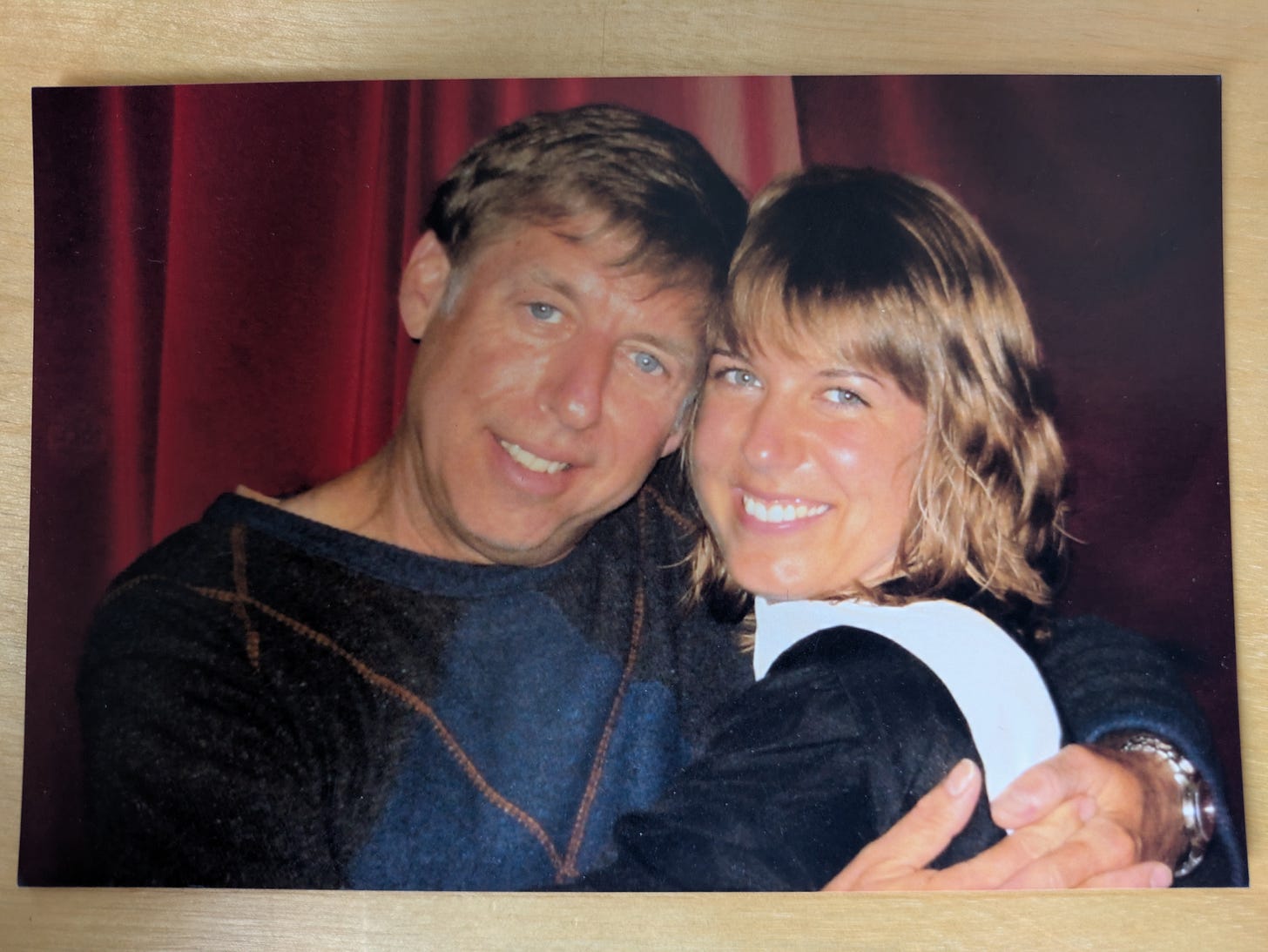

He was only fourteen years older than I am now when he died. I won’t ever get to see him as an old man. His fifty-eight year old self — dirty blonde hair, gray only at the temples, salt and pepper beard — is etched in my mind as his eternal age.

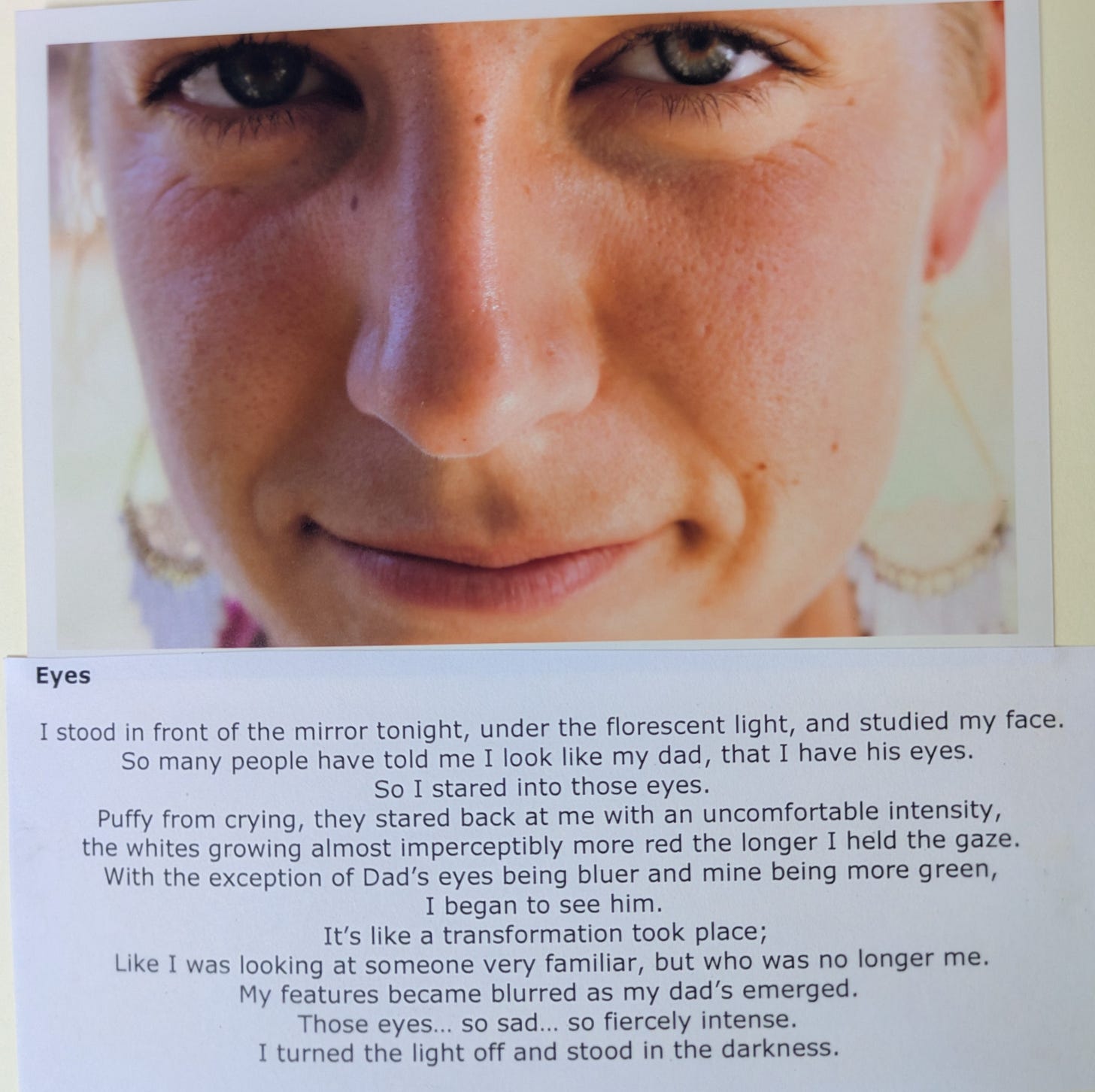

Recently, I found my first gray hair and fingered it with amusement and delight. What will I look like when I’m fifty-eight, I wonder. The older I get, the more I shed my gender conditioning, the more I see his face reflected back in the mirror.

His face, flickering in and out of mine, with his soft penetrating smile, a hint of sadness behind the eyes. Reminding me he is never truly gone and I am never truly without a dad who loves me through my transformations.

Absolutely beautiful and heartbreaking. This brought tears to my eyes. He would be so proud of you and your strength in becoming who you are.

Phoenix, this is stunning.... so much of this intensely resonated with my own experience of grieving my dad. I've been thinking about this a lot lately, I think there's something quietly beautiful about how our relationship with someone we've lost transforms over time. Your Papa is most certainly with you through every cycle and transformation. Thank you for sharing, as always. Thinking about you.